Skip to content

Extreme heat has affected a large region of continental Eastern Africa since mid-February. Extreme daytime temperatures have been recorded in South Sudan particularly affecting people in poor housing and outdoor workers, a very large part of the population.

After dozens of children collapsed with heatstroke in Juba, schools were closed for two weeks nationwide starting February 20 and the population was advised to stay indoors and keep hydrated. Both are a huge challenge for many across the country as houses are often built with iron roofs, lack cooling and electricity and access to clean water. In Juba, a third of the population does not have access to water and only 1% of the city offers green space and shade for people who do not have access to cooling at home. Heatwaves are arguably the deadliest type of extreme weather event and have a large impact beyond mortality, on e.g., morbidity, agriculture, infrastructure, and economic opportunities the death toll is often underreported and not known until months after the event and many other impacts are not systematically assessed. Those reported so far in South Sudan only represent a very small sample of the full impacts. The impacts we do see already disproportionately affect women and girls, and widen the gap between their opportunities and those of men in an already unequal society.

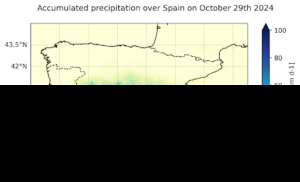

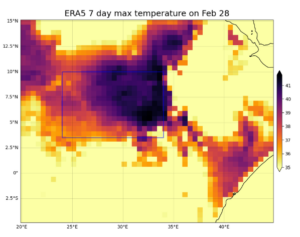

Scientists from Burkina Faso, Kenya, Uganda, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Mexico, Chile, the United States and the United Kingdom collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the extreme heat in the region and to what extent the impacts particularly affected women and girls. The aim of this focus is to suggest pathways for building more equitable climate resilience at a time of year (International Women’s Day) when some international attention is given to the livelihoods of women. Our analysis focuses on a region centred on South Sudan (fig 1), where the highest temperatures were recorded, where we have reported impacts and where the vulnerability to increasingly common heat is particularly high. We focus on the week in February with the most severe maximum temperatures (fig1) calculated as the hottest 7-day daily maximum temperature period in the year.

Main Findings

- In South Sudan, gender plays a crucial role in shaping vulnerability, exposure, and coping capacity to extreme heat events. Women in the country face huge challenges, including high maternal mortality (1,223 women per 100,000 live births), lower adult literacy (29% compared to 40% for men), and are only represented with 32% of the seats in national parliament. Almost all women that have employment are working in the informal sector (95%).

- Women predominantly work in agriculture (or another occupation with high heat exposure, such as street vending or manufacturing) and spend 60% of their time on unpaid care work, such as fetching water, and cooking in extremely hot environments. This sustained heat exposure with physical exertion can have serious long-term health effects, including cardiovascular strain, kidney damage, and increased vulnerability to heat exhaustion and heat stroke.

- Education is severely impacted by extreme heat. Prolonged school closures increase the likelihood of learning losses, reinforce gendered household expectations, and heighten risks of early marriage, making school return more difficult for girls. Actions such as changing the timing of school to avoid the hottest part of the day, or rearranging the academic calendar, suggested by education workers could help avoid long-term closures. Retrofitting school buildings with passive cooling options (e.g. shade trees, painting roofs white) can also be a low-cost way of reducing risks, along with first aid education for teachers and students to recognise the signs of heat-related illness and take appropriate action.

- Malnutrition, already affecting 860,000 children under five in South Sudan, is worsened by extreme heat. Extreme heat worsens food insecurity, weakens immune systems, and increases the risk of dehydration and illness, particularly in children in female-headed households. Limited access to food, healthcare, and income security compounds these vulnerabilities, creating a cycle of worsening health outcomes and deepening inequalities.

- Displacement and conflict heighten heat risks, particularly for women and girls. Armed conflict in the region has forced over 1.1 million people into overcrowded shelters with poor ventilation, worsening heat exposure. Displaced women often lack access to cooling, water, and healthcare and are at heightened risk of violence.

- The hottest temperatures of the year are not usually expected to occur as early as February when this extreme heat was observed. In today’s climate however, which has warmed by 1.3C, the 7-day nighttime and daytime temperatures observed in the South Sudan region are no longer unusual even for February.

- However, the 7-day maximum heat in the South Sudan region would have been extremely unusual in a 1.3C colder climate, if the world had not warmed due to the burning of fossil fuels. Based on observations, extreme heat such as observed in 2025 would have been extremely unlikely to occur in a 1.3C colder climate. A similarly frequent 7-day heat event would have been around 4C cooler in a 1.3C cooler climate.

- When combining the observation-based analysis with climate models, to quantify the role of climate change in this 7-day heat event, we find that climate models underestimate the increase in heat found in observations. We can thus only give a conservative estimate of the influence of human-induced climate change. Based on the combined analysis we conclude that climate change made the extreme heat at least 2C hotter and at least 10 times more likely.

- Due to the known deficiencies in climate models to represent extreme heat, estimating future changes in the 7-day maximum heat over the South Sudan region also only allows us to give very conservative estimates. At a global warming of 2.6C the likelihood and intensity of such events continue to increase.

- While large-scale adaptation remains a challenge, targeted interventions can help communities manage heat risks even in difficult situations and conflict-torn regions. Expanding access to safe water, shaded areas, and cooling spaces – especially in displacement camps and informal settlements – can offer relief. Ajuong Thok refugee camp which shelters over 40,000 people, most of whom are women, is a positive example of better shelter design in this region.

- Adaptation strategies must be designed with conflict and gender considerations in mind to avoid reinforcing existing inequalities. Supporting women farmers with climate-resilient agricultural practices, strengthening labor protections for outdoor workers, and providing financial assistance to vulnerable households can help build coping capacity. Impact-based early warnings are already in development by IGAD, the regional centre, and will be critical for improving preparedness, but last-mile dissemination of warnings and impacts are critical to ensuring that people take lifesaving, self-protective actions.