All products featured on Vogue are independently selected by our editors. However, we may receive compensation from retailers and/or from purchases of products through these links.

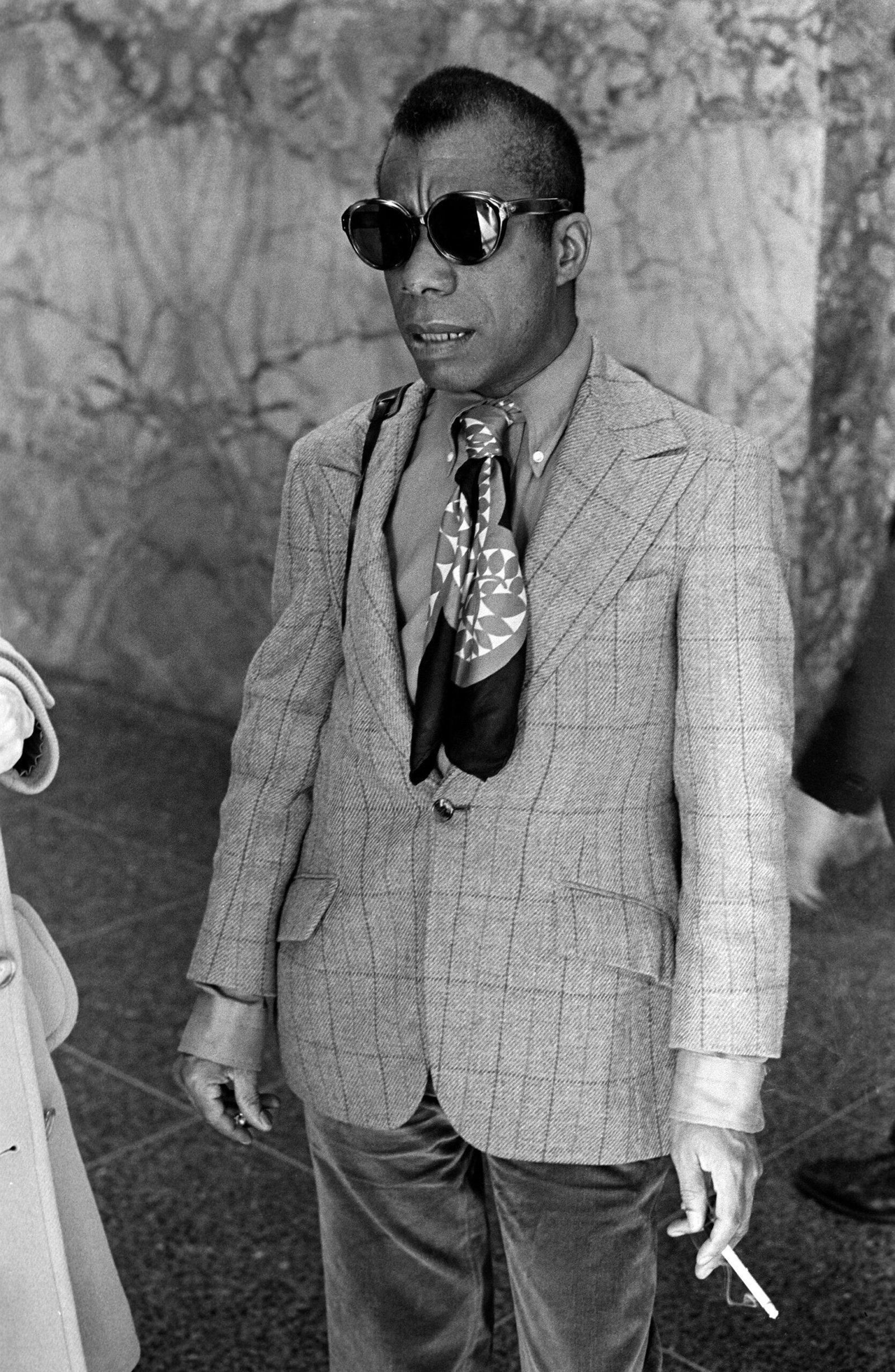

A sharply tailored blazer, oversized sunglasses, a cigarette lit like the period at the end of a sentence: James Baldwin was a writer and a thinker who also understood the power of presentation. And he was not alone. Across the 20th century, a constellation of Black intellectuals and artists approached fashion not merely as ornamentation but as ontology. They dressed with intention, their clothes layered with subtext.

The spring 2025 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” is full of allusions to such figures. Drawing on scholar Monica L. Miller’s 2009 book, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, the show considers how Black people have used dress to shift the way they are seen, spotlighting the work of designers such as Virgil Abloh and Grace Wales Bonner but also the fashions apparent in living rooms and lecture halls and on nightclub stages. As Black intellectuals were reshaping the language of Black life and art, they were also crafting bold visual signatures—through hats, gloves, heels, tuxedos—that projected their thinking into the world.

W.E.B. Du Bois offered a blueprint. In early 20th-century America, where Black manhood was rendered grotesque, Du Bois’s wardrobe was insurgent: gloves, a well-trimmed beard, walking sticks that weren’t just for walking. Dandyism, for him, was not excess; it was evidence. In his seminal 1903 text The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois described double consciousness, the tension of being Black in a country that views you through a veil. His clothes held that tension, transforming theory into form. Every polished shoe and pinstripe was a rebuttal to the caricatures surrounding him.

W.E.B. Du Bois and his wife, Shirley Graham Du Bois, at their home in Brooklyn Heights, 1958

Photo: Getty Images

Zora Neale Hurston carried that sensibility on. Zadie Smith once wrote that she loved Hurston—whose 1934 essay “Characteristics of Negro Expression” inspired the structural framework of “Superfine”—for many reasons but especially for her taste in hats. In a 2009 essay on Hurston’s writing, Smith calls attention to one of her most dazzling self-assessments: “When I set my hat at a certain angle and saunter down Seventh Avenue, Harlem City, feeling as snooty as the lions in front of the Forty-Second Street Library…Peggy Hopkins Joyce on the Boule Mich with her gorgeous raiment, stately carriage, knees knocking together in a most aristocratic manner, has nothing on me. The cosmic Zora emerges. I belong to no race nor time. I am the eternal feminine with its string of beads.” That was Hurston in essence: Born in the segregated South and educated in the North, she refused to belong to either world, instead summoning a force all her own. She rejected the stiff collars of Harlem Renaissance gentility as firmly as the sterile detachment of white anthropologists, dressing up in satin gowns and snakeskin shoes, fur stoles, and feathered caps. Hurston turned selfhood into spectacle.

Zora Neale Hurston at a book fair, circa 1937

Photo: Getty Images

At a football game in 1939

Photo: Getty Images

In the 1940s

Photo: Getty Images

Born a generation later, James Baldwin, like Hurston, did not wear his wounds; instead, he wore sunglasses. Scarves. Coats with sharp collars and clean lines. His wardrobe wasn’t extravagant, but it was exacting, each garment chosen like a well-placed word.

He dressed the way he wrote: with rhythm and always in response to what the world refused to see. In New York, his taste for three-piece suits echoed the careful tailoring of the Harlem Renaissance: square shoulders, fine fabrics. Then, in Paris, he shed the weight. In the late 1940s, the rise of racial violence and McCarthyism, which targeted LGBTQ+ individuals during the so-called Lavender Scare, made life in the United States precarious for Baldwin as a Black queer man. So he fled to Paris, a longtime haven for artists like Josephine Baker and Richard Wright. There, he honed his insights on race, power, and belonging and finished his first published novel—1953’s Go Tell It On the Mountain—and drafted 1956’s Giovanni’s Room as well as several essays in his 1955 collection Notes of a Native Son. He also adopted minimalist trench coats and slim-cut suits that aligned him with the intellectual bohemianism of the Left Bank and the clean, architectural lines soon popularized by Pierre Cardin. Later on, in Istanbul, where he would spend much of the 1960s, Baldwin embraced more fluid silhouettes, his look standing apart from both the uniformed militancy of the Black Panther Party and the psychedelic flamboyance of the counterculture movement at home.

Baldwin sports a dark trench in 1963.

Photo: Getty Images

In 1972

Photo: Getty Images

He never surrendered to full European assimilation, however. The edge of Harlem lingered: a ring, a fitted turtleneck, the way he stood. Baldwin wasn’t trying to disappear, but neither did he want to be fully read. His style was a cipher: queer, cosmopolitan, controlled.

Figures like Du Bois, Hurston, and Baldwin stitched freedom into fabric—not out of vanity but vision. To revisit their style is not nostalgia; it’s instruction, a reminder that to be Black and dressed is to be in theory, in process, alive.

So who carries their energy now? Prince did, for a time. In lace blouses and four-inch heels, he dressed like no one else dared. But his genius was not in extravagance; it was in the way he made space for others to dress their truths, to treat fabric as language and silhouette as statement. Similarly, Iké Udé’s self-portraits are less about fashion than authorship, building a counter-history of Black elegance. Ekow Eshun curates style like a scholar curates theory. Solange Knowles lives in her visuals: chrome, cowries, cloth—none of it arbitrary. And Grace Wales Bonner doesn’t just design but excavates. Her garments are essays in cotton and wool.

But few held the tension between beauty and burden like André Leon Talley, his capes cathedrals, his vocabulary velvet. His presence in the front row wasn’t symbolic—it was seismic.

This lineage is not closed. As Miller reminds us, Black dandyism has long been a tool for reimagining identity and reclaiming humanity. Across the last century, that strategy has unfolded in satin and suede, in cravats and cowries. What began as resistance has become repertoire.