In January, a study published in the journal Nature Medicine suggested that by 2060, the number of Americans with dementia will double to a total of one million. Also doubling: The estimated lifetime risk of developing the condition, compared to previous estimates.

Figures like these can sound scary — and indeed, dementia projections carry some warnings. For one, they suggest the U.S. urgently needs to pour resources into growing its caregiving workforce to meet future needs. But paradoxically, this number also tells a success story.

Today, thanks to decades of social and medical progress, more Americans than ever are living long enough to get dementia; in the past, more people would have died of cardiovascular disease or cancer at earlier ages. These health advances have also delayed the condition’s onset for many people.

Perhaps the most hopeful news about dementia is that there’s a lot people can do to lower their chances of developing it, says Michael Fang, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and lead author of the recent study.

The new study hints at the potential disruption to families, caregivers, and the economy if nothing changes to reduce dementia risk, he says. “But if we do do something, there is an opportunity and a potential to bend the curve a little bit.”

The simple reason dementia rates are on the rise

This study is not the first to project that the number of Americans with dementia is on the rise. However, while past estimates placed the lifetime risk somewhere between 14 and 23 percent, the latest one suggests that more than 40 percent of Americans may develop the condition at some point in their lives.

A care worker helps an elderly woman who suffers with dementia get ready for bed.

Photograph by Steve Forrest, Panos Pictures/Redux

Some of that increase can be explained by the study’s participants, about a quarter of whom are Black (the U.S. as a whole is about 14 percent Black).

“There are lots of papers that show that non-whites have greater risk of getting dementia,” says Kristine Yaffe, a dementia researcher at the University of California, San Francisco.

In the U.S., the higher risk to non-white people stems from poorer access to resources that prevent dementia — like high-quality education, healthy food, and safe outlets for physical activity — and higher smoking rates. For that reason, dementia projections based on data from a somewhat more racially diverse group will be higher than those based on a mostly white group, as most previous studies were.

That said, this study’s participant pool doesn’t explain the entirety of its upgraded risk projections.

Two other big contributors do: More Americans than ever are living into their 80’s and 90’s and reaching the point where they’re more likely to experience cognitive changes.

(What are the signs of dementia—and why is it so hard to diagnose?)

The vast majority of dementia cases occur in older adults. According to Josef Coresh, the study’s senior author and founding director of the Optimal Aging Institute at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, four percent of American 75-year-olds have some form of the disease, and the risk increases steeply in the years that follow. Nearly 20 percent of 85-year-olds have dementia, and the risk continues to rise with every year that follows.

Americans are increasingly likely to reach those late life stages. While people born in the 1950’s could expect to live an average of 69 years, people born in the 2010’s can anticipate an additional decade of lifespan. Women’s lifespans are on average longer than men’s, and it’s in part for that reason that women are more likely to develop dementia at some point in their lives.

A man paints everyday to say active in mind and body to stave off dementia.

Photograph by David Guttenfelder, Nat Geo Image Collection

You can lower dementia risk, no matter how old you are

Dementia isn’t on the rise because it’s getting harder to prevent — quite the opposite, in fact.

The advances that are allowing more Americans to reach old age are also delaying the onset of dementia for many people. In a room full of randomly selected 70, 80, or 90-year-old Americans, fewer would have dementia today than a similar sample of people 50 years ago.

Yaffe says that decrease in age-specific risk is largely due to improvements in many areas, including better cardiovascular health and education. Childhood education and cognitive stimulation over the life course are protective against dementia symptoms. “All these things really changed a lot,” she says.

You May Also Like

These advances — along with lower rates of smoking and alcohol overuse, better air quality, improved treatment for depression, and other quality-of-life changes — likely explain why people who develop dementia today are getting it later in life than people who developed dementia in the 1970’s.

Some risk factors for dementia are not ones we can alter. Most notably, people who carry copies of the apoE gene in their DNA are at higher risk than others for Alzheimer disease, the most common cause of dementia.

However, many dementia risk factors are ones we can change.

Last year, a group of dementia experts published a report listing 14 specific actions people can take to lower their risk across their lives. They include choices to make for children — like encouraging helmet use during sports to reduce brain injury risk— and choices for older adults, like treating vision and hearing loss, and seeking supportive living and social environments to reduce isolation. Several studies have shown these actions’ protective effects can add up.

The Lancet Commission on Dementia recommends several specific actions across the life course to reduce dementia risk:

- Ensure good quality education is available for all and encourage cognitively stimulating activities in midlife

- Make hearing aids accessible for people with hearing loss and decrease harmful noise exposure

- Treat depression effectively

- Encourage use of helmets and head protection in contact sports and on bicycles

- Encourage exercise

- Reduce cigarette smoking

- Prevent, reduce, and treat high blood pressure

- Treat high cholesterol, especially during and after midlife

- Maintain a healthy weight and treat obesity as early as possible, in part to help prevent diabetes

- Reduce high alcohol consumption

- Prioritize age-friendly and supportive community environments and housing and reduce social isolation by facilitating participation in activities and living with others

- Make screening and treatment for vision loss accessible for all

- Reduce exposure to air pollution

Patricia Crowley, who worked on the underlying dataset of the Nature Medicine study, made several of these changes after retiring about a decade ago. Her husband had been diagnosed years before with mild cognitive impairment, a precursor to dementia, and they both joined a local senior center after she stopped working. The strength training, tai chi, tech support, and book exchanges that soon filled their calendars weren’t just about staying busy, she says: “The friendship and the exercise” have been critical to their continued well-being.

The Lancet Commission on Dementia recommends several specific actions across the life course to reduce dementia risk. Exercise is one of them.

Photograph by Joshua Bright, The New York Times/Redux

Lifestyle changes can make a difference, but some of the most powerful preventive interventions experts recommend are pharmaceutical: Medicines to treat high blood pressure and cholesterol can be particularly useful in reducing risk. Some early evidence suggests GLP-1 inhibitors like semaglutide and tirzepatide (Ozempic and Wegovy) may be protective, perhaps due to their effects on brain inflammation.

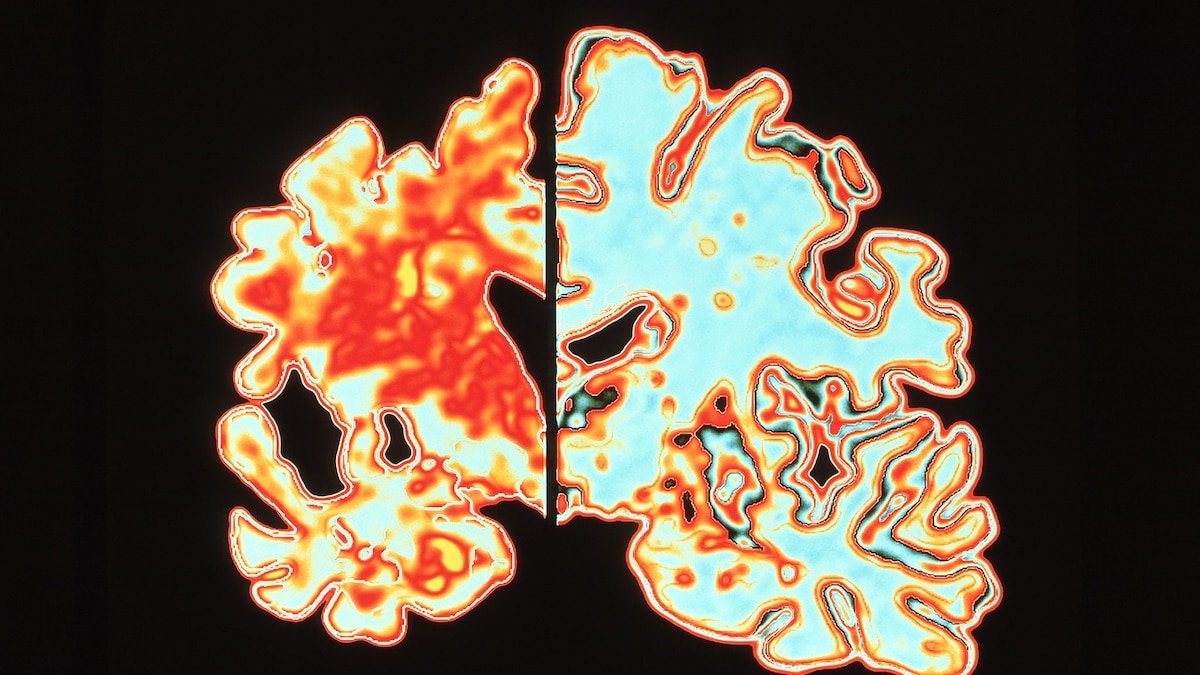

There’s also a lot of interest in understanding whether recently FDA-approved drugs like lecanemab (Leqembi) — which reduce brain buildup of amyloid, the chief culprit in causing Alzheimer disease — can prevent the condition in people who haven’t yet developed dementia symptoms, says Yaffe. Although scientists are currently trying to answer this question, Yaffe doesn’t expect to see study results for five to ten years.

Don’t be afraid to talk about dementia

Unfortunately, stigma surrounding the diagnosis keeps many people from talking to their clinicians when they notice signs of memory loss.

That’s a real shame, says Regina Shih, a dementia epidemiologist at Emory University. “Dementia is not necessarily a death sentence,” she says. “There are a lot of things one can do, both in terms of preventing dementia and also what to do once you have a diagnosis of dementia.” However, patients might not get counseling on those actions if their providers aren’t aware they’re experiencing cognitive changes.

Crowley’s awareness of dementia prevention measures helped her make good choices for herself and her husband. They’re fortunate that for the moment, they don’t require advanced care, which has been in increasingly short supply as the elder care workforce has dwindled.

(Why the new Alzheimer’s drug is eliciting both optimism and caution)

Perhaps just as important as Crowley’s knowledge was her ability to confront reality and make changes to adjust to it, a skill she acquired when she was diagnosed with a chronic eye condition in her early twenties, leaving her legally blind.

“Early on, I realized that you can ruin your own life by not accepting things as they are,” she says – “and the accepting part is the part that makes the difference.”