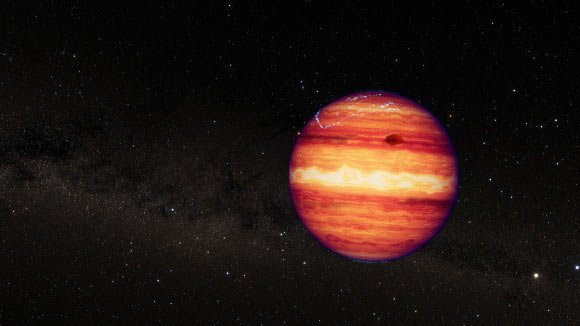

New observations from the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope support the presence of three specific features — clouds, hot spots, and changing carbon chemistry — in the atmosphere of the rapidly rotating, free-floating planetary-mass object SIMP J013656.5+093347.

An artist’s impression of SIMP 0136. Image credit: NASA / ESA / CSA / J. Olmsted, STScI.

SIMP J013656.5+093347 (SIMP 0136 for short) is a rapidly rotating, free-floating object located just 20 light-years from Earth.

It has a mass of 13 Jupiter masses, doesn’t orbit a star and may instead be a brown dwarf.

Because it is isolated, SIMP 0136 can be observed directly and with no fear of light contamination or variability caused by a host star.

And its short rotation period of just 2.4 hours makes it possible to survey very efficiently.

“We already knew that it varies in brightness, and we were confident that there are patchy cloud layers that rotate in and out of view and evolve over time,” said Allison McCarthy, a doctoral student at Boston University.

“We also thought there could be temperature variations, chemical reactions, and possibly some effects of auroral activity affecting the brightness, but we weren’t sure.”

Webb’s NIRSpec instrument captured thousands of individual 0.6- to 5.3-micron spectra of SIMP 0136 — one every 1.8 seconds over more than three hours as the object completed one full rotation.

This was immediately followed by an observation with Webb’s MIRI instrument, which collected hundreds of measurements of 5- to 14-micron light — one every 19.2 seconds, over another rotation.

The result was hundreds of detailed light curves, each showing the change in brightness of a very precise wavelength (color) as different sides of the object rotated into view.

“To see the full spectrum of this object change over the course of minutes was incredible,” said Dr. Johanna Vos, an astronomer at Trinity College Dublin.

“Until now, we only had a little slice of the near-infrared spectrum from Hubble, and a few brightness measurements from Spitzer.”

The astronomers noticed almost immediately that there were several distinct light-curve shapes.

At any given time, some wavelengths were growing brighter, while others were becoming dimmer or not changing much at all.

A number of different factors must be affecting the brightness variations.

“Imagine watching Earth from far away, said Dr. Philip Muirhead, also from Boston University.

“If you were to look at each color separately, you would see different patterns that tell you something about its surface and atmosphere, even if you couldn’t make out the individual features.”

“Blue would increase as oceans rotate into view. Changes in brown and green would tell you something about soil and vegetation.”

To figure out what could be causing the variability on SIMP 0136, the team used atmospheric models to show where in the atmosphere each wavelength of light was originating.

“Different wavelengths provide information about different depths in the atmosphere,” McCarthy said.

“We started to realize that the wavelengths that had the most similar light-curve shapes also probed the same depths, which reinforced this idea that they must be caused by the same mechanism.”

One group of wavelengths, for example, originates deep in the atmosphere where there could be patchy clouds made of iron particles.

A second group comes from higher clouds thought to be made of tiny grains of silicate minerals.

The variations in both of these light curves are related to patchiness of the cloud layers.

A third group of wavelengths originates at very high altitude, far above the clouds, and seems to track temperature.

Bright hot spots could be related to auroras that were previously detected at radio wavelengths, or to upwelling of hot gas from deeper in the atmosphere.

Some of the light curves cannot be explained by either clouds or temperature, but instead show variations related to atmospheric carbon chemistry.

There could be pockets of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide rotating in and out of view, or chemical reactions causing the atmosphere to change.

“We haven’t really figured out the chemistry part of the puzzle yet,” Dr. Vos said.

“But these results are really exciting because they are showing us that the abundances of molecules like methane and carbon dioxide could change from place to place and over time.”

“If we are looking at an exoplanet and can get only one measurement, we need to consider that it might not be representative of the entire planet.”

The findings appear in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

_____

Allison M. McCarthy et al. 2025. The JWST Weather Report from the Isolated Exoplanet Analog SIMP 0136+0933: Pressure-dependent Variability Driven by Multiple Mechanisms. ApJL 981, L22; doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ad9eaf