Chief Ben Barnes of the Shawnee Tribe based in Miami, Oklahoma, spends a lot of time thinking about Kansas. There, in a small town called Fairway, three red-brick buildings sit aging on land once allotted to his tribe.

These Federal-style structures are what remain of what was once called the Shawnee Indian Manual Labor Boarding School. It was among the earliest of a federally supported system of residential schools intended to assimilate Indigenous children into American culture – and force them to leave their own behind.

Like Mr. Barnes, many members of the Shawnee Tribe can trace their ancestry to those who once lived in what he calls a “child work camp.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

Last year, the U.S. government apologized for trying to erase Native American culture in its policies toward Indian boarding schools. Indigenous tribes like the Shawnee want to tell the story from their perspective.

Today the site is owned by the Kansas Historical Society, a state agency. Now called the Shawnee Indian Mission State Historic Site, it is run by officials in the city of Fairway. With funding help from a local foundation, these partners help run a decades-old museum in one of the 19th-century-era buildings.

Five years ago, Mr. Barnes began to cooperate with the Kansas Historical Society, and later he accepted a seat on the local foundation’s board as officials were planning a significant renovation and expansion.

Together, each group was eager to transform the site. They all wanted to build a state-of-the art museum and tell the story of the boarding school better. The Shawnee would play a significant part throughout this process, and have a permanent role.

But this enthusiastic cooperation eventually turned into an abyss of mistrust.

The Shawnee Indian Mission West Building is seen from the porch of the North Building in Fairway, Kansas. The West Building served as a classroom and as living quarters for Indian Manual Labor Boarding School teachers.

Until recently, the history of U.S. boarding schools for Indigenous children has mostly been forgotten. But here in Kansas and other places where such school buildings still stand, there’s momentum to delve more deeply into this dark part of America’s past. Mr. Barnes, like other Native leaders around the country, has begun to learn details about his ancestors that he hadn’t known before.

When historians came in to study the Shawnee Indian Manual Labor Boarding School’s archives, their findings made his relatives of older generations come alive for him, in important and complicated ways. And the more he learned, the more he found he could not share the vision the other parties had for commemorating a common past.

For very practical reasons, plans for the site aimed to include opportunities to raise awareness and much-needed funds. And since the site was already a National Historic Landmark for a number of reasons, the other partners wanted to expand the kinds of civic events it hosted, such as yoga classes, concerts, a fall festival, and Christmas tree sales. A large pavilion for these activities was being considered.

These ideas appalled Mr. Barnes. Then, he discovered, there were YouTube clips posted by local paranormal investigators who had rented space. They were holding a séance on the site, speculating whether they were communicating with spirits of Indigenous children.

On top of that, he had concerns about the overall upkeep at the site, and he began to grow concerned about the conditions of the buildings.

Mr. Barnes soon resigned from the foundation’s board and withdrew Shawnee participation from the project.

Today he is urging Kansas state legislators to transfer ownership of this site to his tribe – a measure lawmakers are currently considering. His own plan is to turn all three buildings into a museum that would address all chapters of the mission’s history. The darkest chapter, the history of the boarding school era, would be told from a tribal perspective.

Cobbling tools used by boys at the Indian Manual Labor school fill a display case at the Shawnee Indian Mission State Historic Site in Fairway, Kansas.

“We have a responsibility. It’s not just honoring the dead, but we have to speak on their behalf, take care of their concerns while they’re on the other side and we’re here,” Mr. Barnes says.

“I find myself having to do that with these people that went to the mission, whether they survived or not. Yes, the majority survived, but none of them, none of them really survived.”

The uncomfortable truths of U.S. and Native American history

Chief Barnes also spends a lot of time thinking about Dave Deshane.

He was Mr. Barnes’ great-great-great-grandfather. He had a son, Peter Deshane, the chief’s great-great-grandfather.

Historians had been delving deeper into the former boarding school’s records. One of them sent Mr. Barnes what he’d found about the Deshanes.

In the 1850s, he found, Peter Deshane was repeatedly escaping from the boarding school.

Each time, the missionaries who ran the residential school on Shawnee “Indian land” would go out to retrieve him, knowing he usually just went back home. But the boy’s father eventually told them to stop. He would take care of the problem himself.

When Peter ran away again, his father tied his son’s hands to a horse’s tail and dragged him back to the mission. Peter never ran away again.

The story has shaken Mr. Barnes. “I saw the names, and like, man, this is my people,” says Mr. Barnes, who simply recognized them from family trees. “So that was pretty heavy, to read about your people.”

He had to wrestle with his own ambivalence. “I saw the story through the kid’s eyes at first – what that betrayal must have felt like,” he says. “It took some time to really digest what the perspective of the father must have been.”

The Indian Manual Labor Boarding School North Building served as a dormitory for girls and a space for classrooms.

It’s also difficult to digest the larger history of American policy governing boarding schools for Indigenous children. For the Shawnee, the history of these policies is indeed a dark history – and part of the American story long ignored.

Between 1819 and 1969, about 400 federally funded boarding schools operated nationwide, according to a landmark 2024 report by the U.S. Department of the Interior. At least 18,600 Indigenous children attended these schools, and at least 973 died while living there, the study found – some of them buried in unmarked graves.

“Though it is uncomfortable to learn that the country you love is capable of committing such acts, the first step to justice is acknowledging these painful truths and gaining a full understanding of their impacts so that we can unravel the threads of trauma and injustice that linger,” wrote former Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, revealing that her maternal grandparents and great-grandfather had been forcibly separated from their families and culture.

Acknowledging such painful truths, too, is the first step to healing. After the report was released, she helped lead a 12-city “tour of healing” in which Native American peoples could publicly share with the U.S. government such threads of trauma inflicted for almost two centuries.

In October last year, President Joe Biden issued an official apology for this U.S. policy toward Indigenous peoples.

“The federal Indian boarding school policy, the pain it has caused, will always be a significant mark of shame, a blot on American history,” Mr. Biden said on tribal land at the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona.

“I formally apologize as president of the United States of America for what we did,” he said. “It’s long overdue.”

Not all schools started out the same, however. Early ones, like the Shawnee mission school during its first years, were church-run day schools located on reservations. Attendance was voluntary, and sometimes Native leaders requested schools for their reservations.

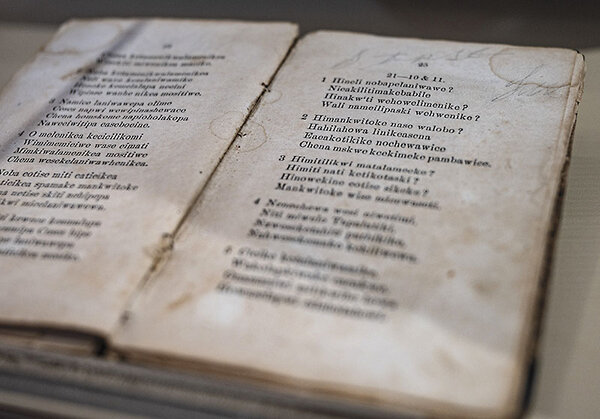

A 19th-century Shawnee-language Bible sits on display at the Shawnee Indian Mission State Historic Site in Fairway, Kansas. Indigenous students were taught Christianity and forbidden to practice their tribal religions.

But that changed as federal officials began to shape these schools with policies of family separation and assimilation, focusing specifically on children.

If Indigenous peoples were really going to integrate into American Protestant society, the country would need to seek the “complete isolation of the Indian child from his savage antecedents,” according to one Bureau of Indian Affairs report to the Interior Department in 1886.

This family separation policy included stripping incoming students of nearly every aspect of their identity. They were given English names. Speaking their native languages and wearing traditional clothes was forbidden. They were taught Christianity and banned from following Indigenous practices.

The founder and head of the notorious Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, Brig. Gen. Richard Pratt, put the policy bluntly: “All the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, save the man.”

By 1891, Congress authorized federal agents to forcibly remove Indigenous children from their homes, sending them – often against their families’ wishes – to distant off-reservation schools like Carlisle, where conditions were often brutal. Military drills were routine, and abuse was widespread.

Mr. Barnes still wrestles with what Dave Deshane did to his son Peter. But in a way, the enormity of Indigenous history in the U.S. can make him understand, if just a bit.

“You have the father who’s looking at the world, through adult eyes, and saying, ‘Son, you don’t know what this world’s like. I’m sorry. This is the least worst option for you. You think this is bad for you, but you don’t know what bad is.’”

Ben Barnes, chief of the Shawnee Tribe in Miami, Oklahoma, stands outside its headquarters Jan. 9, 2025. “We have a responsibility,” he says. “It’s not just honoring the dead, but we have to speak on their behalf.”

Who should control Native American history?

When Nathan Nogelmeier took a job as Fairway’s city administrator eight years ago, he thought he knew what to expect.

Most days would be spent on budgets, City Council meetings, and staff management in Fairway – a small, affluent, and mostly white community of 4,000.

Instead, he’s found himself in what can feel like a crash course in the Shawnee mission’s history.

Mr. Nogelmeier started working for the city in 2003 – essentially as a part-time Parks and Recreation director. “I was immediately fascinated with the Shawnee Indian Mission,” he says. And when his job became full time in 2005, “One of the first things I wanted to do was to beef up our programs that we partnered on at the mission.”

As part of his job, he would facilitate some of the sponsored events at the historic site. These included overnight “Daddy and Me” campouts. “There was something about being on the grounds at night, you know, just knowing its history and knowing that it was untouched,” Mr. Nogelmeier says.

Nathan Nogelmeier, city administrator for the town of Fairway, Kansas, stands behind Mayor Melanie Hepperly in the Shawnee Indian Mission chapel, Jan. 8.

“When you walk on the site and you look around, and you look at the buildings, you look at the trees that are there, it’s significant. Like, you just feel it,” he says. “I was not aware of that history up until about three years ago, when I really started digging into the history of the site.”

But as the conflict with the tribe began to escalate, his boss, part-time Mayor Melanie Hepperly, tasked him with making the case that Fairway and the state of Kansas should continue to maintain control of the mission site – a position backed by the Fairway City Council.

(Patrick Zollner, executive director of the Kansas Historical Society, declined to comment on the dispute, referring questions to Mr. Nogelmeier. The agency’s official position is that the city, state, and foundation should continue their partnership.)

“Whether or not you agree with the detail and scope of what they’ve done, the Kansas Historical Society has maintained those three buildings for nearly 100 years,” says Mr. Nogelmeier, who is now, in effect, the government’s spokesperson when it comes to Chief Barnes’ efforts to take control of the site.

“They are in charge of 16 sites across the state,” he says. “I’m not sure that the tribe would be able to match that level of expertise.”

Yes, renting buildings to paranormal investigators trying to conjure former students was regrettable, Mr. Nogelmeier says. But hosting mission-run events with other paranormal groups was simply a moneymaking effort, and the city halted them when it realized they could be offensive. (Later, the city and foundation realized such events violated historical society rules.)

Mr. Nogelmeier also worries that if the Shawnee take ownership of the land, the full history of the mission site might be lost.

These buildings were also once the location of one of Kansas’ early territorial capitols. The site was a supply station on the Santa Fe and Oregon trails and later barracks for Union soldiers after the school closed for good during the Civil War.

Civil War artifacts sit on display in the museum at the Shawnee Indian Mission State Historic Site, Jan. 8, 2025.

“The Shawnee Tribe definitely has a story to tell about the Shawnee Indian Mission,” Mr. Nogelmeier says. “But there were 21 other tribes with students here. Don’t they deserve an equal say?”

From 1839 to 1862, about 60 to 120 students attended the school annually, ranging from ages 5 to 23. Though the Shawnee made up about 40% of the students, 21 other tribes, including the Kaw, sent their children there as well. A few white students, the children of staff, as well as Black enslaved students also attended the school.

The Kaw Nation, the original inhabitants of this part of Kansas, also opposes the Shawnee plan to take over the site. In January 2024, the Kansas House held a hearing on the bill, which eventually died in committee. Ken Bellmard, the Kaw Nation’s government affairs director, was among those who testified against it.

“It might have been theirs for 20 years as a boarding school, but it was ours from time immemorial,” Mr. Bellmard says in an interview with the Monitor. “If they’re giving the land back, it should go to us.”

The issue of possible unmarked graves on the site has given the dispute its most visceral edge. Before the early partnership with the Shawnee collapsed, Mr. Barnes had begun to press the issue as paramount.

Artifacts conveying pioneer life sit on display in the museum at the Shawnee Indian Mission State Historic Site, Jan. 8, 2025.

Hundreds of unmarked graves were discovered on Indigenous residential school sites in Canada around this time. Tribes there had used ground-penetrating radar to survey school properties. Like those in the U.S., these boarding schools in Canada were meant to strip Indigenous children of their traditional cultures and make them Canadians. In public comments, Mr. Barnes said he also wanted to use radar to do the same.

There is no evidence that there are unmarked graves, or any graves, at the Shawnee Indian Mission State Historic Site. Still, the issue is complicated. When the boarding school was operational in the 19th century, it spanned 2,000 acres, compared with its present 12. Three tribal cemeteries sit just outside its original borders, areas now dotted with large, upscale homes.

Mr. Nogelmeier and Mayor Hepperly were taken aback when Mr. Barnes raised the idea of a search. This had never been an issue before, and they assumed all children had been buried in the tribal cemeteries located relatively close to the former mission site.

Eventually the Kansas Historical Society agreed to move forward with such a radar search. However, Mr. Barnes then balked, arguing the society’s plans to survey the site did not have sufficient tribal input.

There may be another reason. If a survey found the graves of Kaw children on the mission site, for example, the Shawnee effort to own the site could be complicated.

The history of the Shawnee Indian Manual Labor Boarding School

Of the three buildings of the former Indian Manual Labor Boarding School property, only one, the East Building, is open to the public. The first floor of that building has one room dedicated to the Indigenous boarding school era.

Last updated by the Kansas Historical Society 25 years ago, the displays include relics of daily life: a set of well-worn tools once gripped by young hands, the iron bell that summoned students to meals, a brittle Bible translated into Shawnee. The exhibit also displays the wooden pulpit they may have gazed up at during Methodist services.

Displays hung on white walls veined with cracking plaster touch on the tribe’s history. But there’s no information about the consequences of the boarding schools, no names and faces of children who went there, and no mention of the Shawnee today.

Upstairs, there are five rooms with equally dated exhibits. Divided thematically, they focus on federal Indian agents who represented the U.S. government, pioneer life in the 19th century, and the site’s role during the Civil War.

Other exhibits commemorate one of the Kansas Territory’s early legislatures, which met here. And there is plenty of information about the Shawnee mission’s founder, Methodist minister Thomas Johnson, a slaveholder from Virginia.

The history of the mission can be traced to 1825, when the U.S. government forced the Shawnee out of Missouri, moving them farther away from their ancestral homeland in the Ohio Valley. In exchange, they were given 1.6 million acres in eastern Kansas – then called Indian Territory.

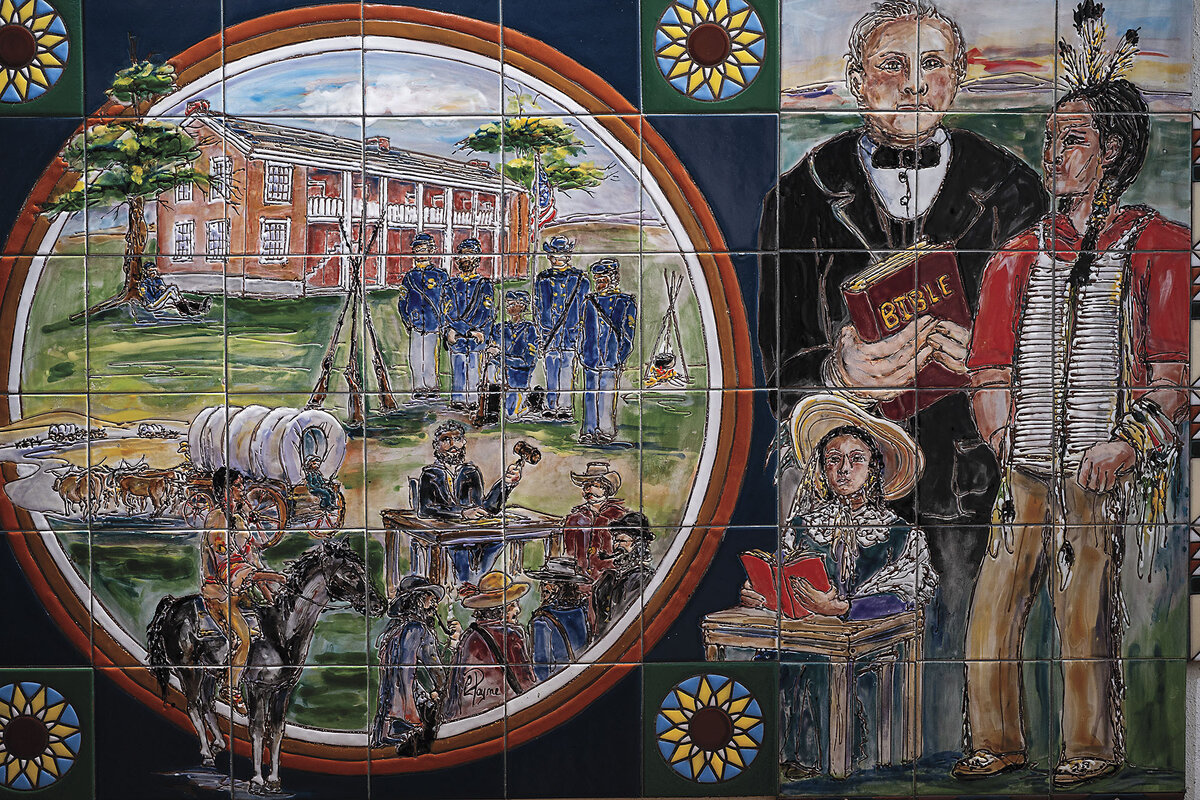

A tile mural depicts past events on school grounds, which are now part of the Shawnee Indian Mission State Historic Site in Fairway, Kansas.

In 1830, likely seeing it as a means of survival, a Shawnee chief invited a missionary to the reservation to help educate members of his tribe in the ways of white Americans. He could not have foreseen the complex history that would follow.

After the Reverend Johnson arrived, the new minister oversaw the construction of the Shawnee Methodist Mission and began a day school for the tribe’s children. By 1839, he had attained federal approval and funding to build a larger manual-

labor boarding school to enroll students from several tribes.

Days were grueling: six hours of study and six hours of “vocational training.” Girls worked in kitchens and sewed; boys farmed, did carpentry, and practiced blacksmithing.

Students worked for free. Any money they made from sales to the community, then a bustling frontier post, went back to the school – and likely into Johnson’s pockets. Tuition was taken from tribal education funds provided by the U.S. government.

Some missionaries viewed their students with a measure of disgust. One teacher referred to Indigenous children as “debased savages” and “heathens,” according to “Annals of the Shawnee Methodist Mission,” a publication by the Kansas Historical Society.

By 1859, pro-slavery settlers were battling antislavery settlers for dominance and land – in a time called “the era of Bleeding Kansas.” Johnson, now very wealthy and a high-profile public figure, was fiercely advocating to make Kansas a slave state.

That same year, facing intimidation by land-hungry settlers, the Shawnee signed another treaty ceding most of their Kansas reservation to the government, leaving the area around the mission to the Methodist church. Little by little, the tribe made its way to modern-day Oklahoma, the new Indian Country.

The school closed in 1862, during the Civil War. In 1865, Johnson was shot to death by unknown assailants at his home.

The mission fell into private hands and began to deteriorate until the 1920s. Then a group of women preservationists in Fairway lobbied the state to save it.

After a legal battle that reached the U.S. Supreme Court, Kansas acquired the former Shawnee mission property in 1927. In 1968, the site became a National Historic Landmark – the highest federal recognition of a property’s historical significance.

The U.S. government sponsors a “Road to Healing” tour

On July 9, 2022, Chief Barnes was among the first to speak at the federally sponsored Road to Healing tour organized by former Interior Secretary Haaland.

The purpose of her department’s landmark study on America’s Indian boarding schools, she said, was to take the first step to justice by acknowledging painful truths.

It was also a first step to healing, she believed.

Mr. Barnes has spent a significant part of his life trying to revive the Shawnee language and religious practices. He is among just a few who still can speak some Shawnee. So when he stood before the audience at Riverside Indian School in Anadarko, Oklahoma, the first stop on the federal government’s Road to Healing tour, he spoke in his native tongue to open his address before switching to English.

“The legacy of boarding schools and removal from families is real, present, and existential,” he said. “Coming just to Riverside and other schools is not going to be enough. … There needs to be a national system for them to bear testimony and send testimonies in it. … That needs to be the norm because for a lot of our people, they don’t want to be anywhere close to the site of their rape. And I apologize for that word. I apologize for that word, but that’s what it was.”

That makes healing difficult, especially after centuries of violence in a country with an official policy of cultural erasure. The story of the former Indian Manual Labor Boarding School in Kansas is not just central to Shawnee history, he argues. It is central to America’s, woven into the fabric of a nation built on the dispossession of Indigenous peoples.

This is why he is battling for his people to control the National Historic Landmark site in Fairway, where the school’s three buildings still bear the dark history of the Shawnee in Kansas.

“We understand how a monument can become sacred, but for whatever reason, we find difficulty that Shawnee people can find this place sacred,” Mr. Barnes says. “What makes it sacred? The fact that it still stands makes it sacred. The fact that those stories need to be told makes it sacred.”