Skip to content

follow a worsening humanitarian situation in eastern DRC, where ongoing violence has

resulted in thousands of deaths and the displacement of millions since January. Image by MONUSCO/Aubin Mukoni

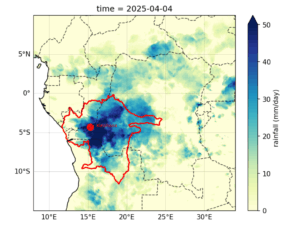

Since April 4, heavy rainfall has been impacting the Democratic Republic of the Congo, triggering widespread flooding, casualties, and extensive damage.

At least 33 people died in the capital, Kinshasa, after the Ndjili River overflowed. The floods have destroyed roads and homes, caused power outages, and severely disrupted the water supply. According to media reports, nearly half of Kinshasa—26 districts—have been severely affected, with floodwaters submerging key infrastructure, including the main road to the airport. The hardest-hit areas are the poorer outskirts of the city (BBC, 2024). In at least 16 communes, access to drinking water has been cut off due to submerged water facilities (NPR, 2025).

The downpours from the 4th of April and over the subsequent days followed unusually heavy rains at the end of March, leading to high rivers even before the rainfall that led to the reported flooding.

Researchers from the DRC, Rwanda, Kenya, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, the United States and the United Kingdom collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the 7-day rainfall that ultimately led to the flooding in Kinshasa. Spatially, the analysis is focussed on the river basin where the Ndjili river and the Congo river combine, which includes other cities than Kinshasa, but while the heavy rain affected large parts of the region, the impacts were concentrated in Kinshasa, the capital of DRC. The assessment of vulnerability and exposure is thus focussed on Kinshasa.

Main findings

- Kinshasa is prone to frequent and deadly flooding during the rainy season (October to May). It is built next to the Congo River and several rivers run directly through the city, including the Ndjili. With close to 18 million residents, Kinshasa is one of the most populated cities in the world. Around 70% of the urban population lives in dense informal housing, much of it in areas prone to floods and landslides. In 2022, more than 100 people died following a similarly heavy downpour.

- From a hazard point of view, the event as observed in 2025 is not rare. Similar periods of heavy rainfall are expected to occur on average every second year in today’s climate, which has been warmed by 1.3°C, due to the burning of fossil fuels.

- To assess whether such heavy rainfall events would have been more or less frequent in the past we assess three gridded data products, as well as two weather stations located in Kinshasa. All three gridded datasets show very different trends, including one that suggests climate change made the event much more likely, while two show no change. The station data is only available until 2023, so does not include the event, but shows different events and trends in the overlapping years than all three gridded products.

- Climate models also show very varying trends, including a strong increase, no trends and a decreasing trend in heavy precipitation over the region since the pre industrial climate. However, this is no indication that there is no trend, as the discrepancies are very high.

- We thus conclude that we cannot provide an attribution statement, but that the possibility of an important role of climate change can also not be excluded and thus need to be included in adaptation and resilience planning.

- The scarcity and inaccessibility of meteorological data, as well as inadequate performance of climate models means that we cannot confidently evaluate the role of climate change in the rainfall that led to flooding. Our previous study on a 2023 flood in Eastern DRC was similarly inconclusive for the same reasons, highlighting an ongoing need to invest in weather monitoring stations and climate science to understand changing weather extremes in Central Africa.

- The IPCC projects an increase in heavy rainfall across Central Africa, particularly over short timescales of five days or less. Several data sources—including two weather stations—and about half of the climate models analyzed indicate a notable rise in heavy rainfall for both Kinshasa and the broader study region. Therefore, a future increase in heavy rainfall due to climate change is a strong possibility.

- Since gaining independence in 1960, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has faced decades of political instability and conflict. Despite being one of the most mineral-rich countries in the world—with over half of the global cobalt supply, a key element in batteries and the global transition to renewable energy—the DRC remains the fourth poorest country globally.

- Prolonged conflict, particularly in the eastern regions (see WWA’s other study in the DRC), continues to severely impact the country. In recent months, violence has intensified, resulting in thousands of deaths and displacing nearly seven million people. These ongoing crises in the east could have far-reaching ripple effects, such as increasing migration flows into cities.

- Floods in Kinshasa, which occur frequently and often result in high death tolls, highlight the urgent need to build resilience to heavy rainfall events. This urgency is further amplified by the city’s rapid growth: Kinshasa’s population is projected to double to nearly 40 million within the next 20 years.

- Flood risk is amplified by rapid population growth, limited infrastructure coverage, and high reliance on informal systems – particularly in areas where critical services such as drainage, healthcare, and electricity remain inconsistent or difficult to access. Drainage is frequently blocked by waste pollution, and there is limited waste management services and sewage maintenance, increasing flooding.

- While progress is being made, for example, the drafting of a new law on the DRC’s town planning and construction code that could reduce flood exposure, more comprehensive efforts are needed to reduce the impacts of very devastating, but common floods. Adaptation finance will be critical to support the country’s flood adaptation measures as population growth in Kinshasa and surrounding cities continues.