Black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus), small North American passerine birds that live in deciduous and mixed forests, have extraordinary memories that can recall the locations of thousands of morsels of food to help them survive the winter. Now, scientists at Columbia University’s Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute have discovered how the chickadees can remember so many details: they memorize each food location using brain cell activity akin to a barcode.

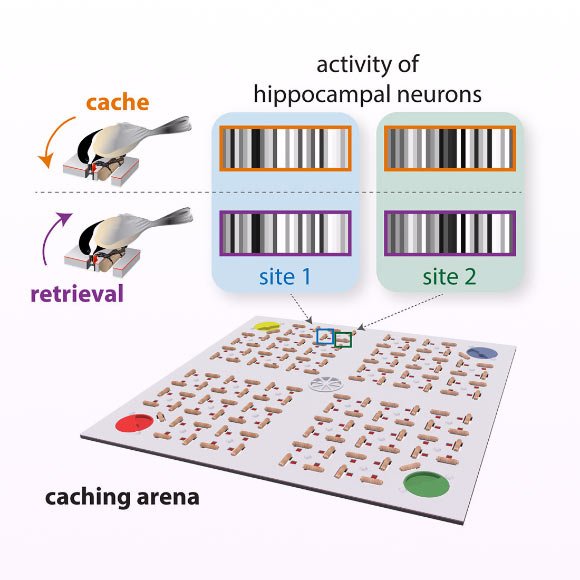

Chettih et al. propose that animals recall episodic memories by reactivating hippocampal barcodes. Image credit: Chettih et al., doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.02.032.

“We find that each memory is tagged with a unique pattern of activity in the hippocampus, the part of the brain that stores memories,” said Dr. Dmitriy Aronov, senior author of the study.

“We called these patterns ‘barcodes’ because they are extremely specific labels of individual memories — for example, barcodes of two different caches are uncorrelated even if those two caches are right next to each other.”

“There are many findings in humans that are totally consistent with a barcode mechanism,” added Dr. Selmaan Chettih, first author of the study.

Scientists have known for decades that the hippocampus of the brain is required for episodic memory, but it had been much harder to understand exactly how those memories were encoded.

That’s in part because it’s hard to know in most cases what an animal might be remembering at a particular time.

To get around this problem in the new study, Dr. Aronov and his colleagues looked to chickadees.

They realized chickadees offered a unique opportunity to study episodic memories because the birds cache food items and then must remember to go back for them later.

“Each cache is a well-defined, overt, and easily observable moment in time during which a new memory is formed,” Dr. Aronov said.

“By focusing on these special moments in time, we were able to identify patterns of memory-related activity that had not been noticed before.”

The researchers had to engineer arenas that allow detailed and automated tracking of behavior as chickadees cache and retrieve food.

They also had to develop technologies for large-scale, dense neural recordings in their brains as the birds moved about freely.

Their brain recordings during caching revealed very sparse, transient barcode-like patterns of firing across hippocampal neurons. Each barcode involves only about 7% of the cells in the hippocampus.

“When a bird makes a cache, about 7% of the neurons respond to that cache. When a bird makes a different cache, a different group of 7% of neurons respond,” Dr. Aronov said.

Those neural barcodes happened together with conventional activity of neurons in the brain that are triggered in response to particular places, appropriately called place cells.

But, interestingly, the episodic memory barcodes for caching locations that were close to each other had no resemblance.

“It was widely assumed that when an animal forms a new memory, place cells change,” Dr. Aronov said.

“For example, place cells might increase or decrease their firing near the location of a cache.”

“Although this was the prevailing hypothesis, our data did not support it.”

“It seems that place cells do not represent information about caches and rather remain relatively stable as a chickadee caches and retrieves food in the environment.”

“Instead, episodic memories are represented by an additional pattern of activity — the barcode — which coexists with place cells.”

The authors liken the newly discovered hippocampal barcodes to computer hash codes, which are patterns assigned as unique identifiers to different events.

They suggest that the barcode-like patterns could be a mechanism for rapid formation and storage of many non-interfering memories.

“Perhaps the biggest outstanding question is whether and how barcodes are used by the brain to drive behavior,” Dr. Aronov said.

“It’s not clear whether chickadees activate the barcodes and use those memories of food-caching events as they make decisions about where to go next, for example.”

“These are questions we plan to address in future studies through more complex environments in the lab in which we’ll record brain activity while the birds make choices about which food caches to visit.”

“That’s what we might expect if they are planning to retrieve a cached item before they actually do it,” Dr. Chettih said.

“We want to identify those moments when a bird is thinking about a location but it’s not there yet, and see if activating a barcode might drive a bird to go to a cache.”

“We are also eager to know if the barcoding tactic they have uncovered chickadees is in widespread use among other animals, including humans. Such research may help shed light on a core part of the human experience.”

“If you think about how people define themselves, who they think they are, their sense of self, then episodic memories of particular events are central to that. That’s what we’re trying to understand.”

A paper on the findings was published in the journal Cell.

_____

Selmaan N. Chettih et al. Barcoding of episodic memories in the hippocampus of a food-caching bird. Cell, published online March 29, 2024; doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.02.032