New research led by Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology scientists challenges conventional ideas about the habitability of ancient tropical forests and suggests that West Africa may have been an important center for the evolution of our species, Homo sapiens.

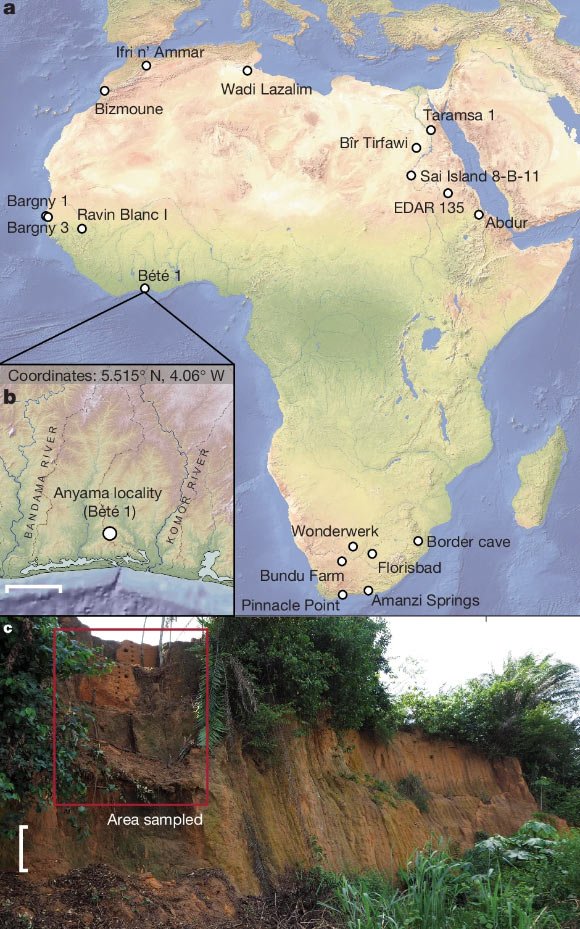

The site of Bété I in Côte d’Ivoire and other African sites dated to around 130,000-190,000 years ago. Image credit: Arous et al., doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-08613-y.

Homo sapiens is thought to have emerged in Africa around 300,000 years ago before dispersing all over the world.

Humans were living in rainforests in Asia and Oceania as early as 45,000 years ago, but the earliest evidence linking people to rainforests in Africa dated to around 18,000 years ago.

“Our species is thought to have emerged shortly before 300,000 years ago in Africa, before dispersing to occupy all the world’s biomes, from deserts to dense tropical rainforest,” said Dr. Eslem Ben Arous, a researcher at the National Centre for Human Evolution Research and the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, and colleagues.

“Although grasslands and coasts have typically been given primacy in studies of the cultural and environmental context for human emergence and spread, recent evidence has implicated several regions and ecosystems in the earliest prehistory of our species.”

“Rainforest habitation in Asia and Oceania is firmly documented as early as 45,000 years ago, and perhaps as early as 73,000 years ago.”

“However, the oldest secure, close human associations with such wet tropical forests in Africa do not date beyond around 18,000, despite evidence of the widespread presence of middle Stone Age assemblages in regions of present-day African rainforest.”

In their research, Dr. Arous and co-authors focused on the archaeological site of Bété I at the Anyama locality of Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa

This site dates to 150,000 years ago and contains signs of human occupation, including stone tools such as picks and smaller objects.

“Several recent climate models suggested the area could have been a rainforest refuge in the past as well, even during dry periods of forest fragmentation,” said Professor Eleanor Scerri, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology.

“We knew the site presented the best possible chance for us to find out how far back into the past rainforest habitation extended.”

The researchers investigated sediment samples from Bété I for pollen, silicified plant remains called phytoliths, and leaf wax isotopes.

Their analyses indicated the region was heavily wooded, with pollen and leaf waxes typical for humid West African rainforests.

Low levels of grass pollen showed that the site wasn’t in a narrow strip of forest, but in a dense woodland.

“This exciting discovery is the first of a long list as there are other Ivorian sites waiting to be investigated to study the human presence associated with rainforest,” said Professor Yodé Guédé, a researcher at the l’Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny.

“Convergent evidence shows beyond doubt that ecological diversity sits at the heart of our species,” Professor Scerri added.

“This reflects a complex history of population subdivision, in which different populations lived in different regions and habitat types.”

“We now need to ask how these early human niche expansions impacted the plants and animals that shared the same niche-space with humans.”

“In other words, how far back does human alteration of pristine natural habitats go?”

The study appears today in the journal Nature.

_____

E. Ben Arous et al. Humans in Africa’s wet tropical forests 150 thousand years ago. Nature, published online February 26, 2025; doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-08613-y